Clips

Remembering Mary Ware Dennett

Remembering Mary Ware Dennett

Published by The Columbia Paper, November 4, 2022

Following her talk at Chase’s Mill in the summer of 2022 in Alstead, NH, Sharon Spaulding was interviewed by Russ Immarigeon about Mary Ware Dennett for The Columbia Paper.

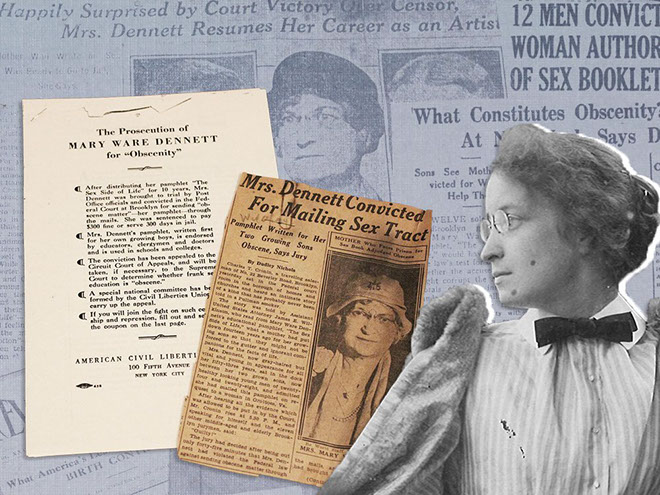

Mary Ware Dennett, circa 1914. Photo Courtesy Dennett Family Archives

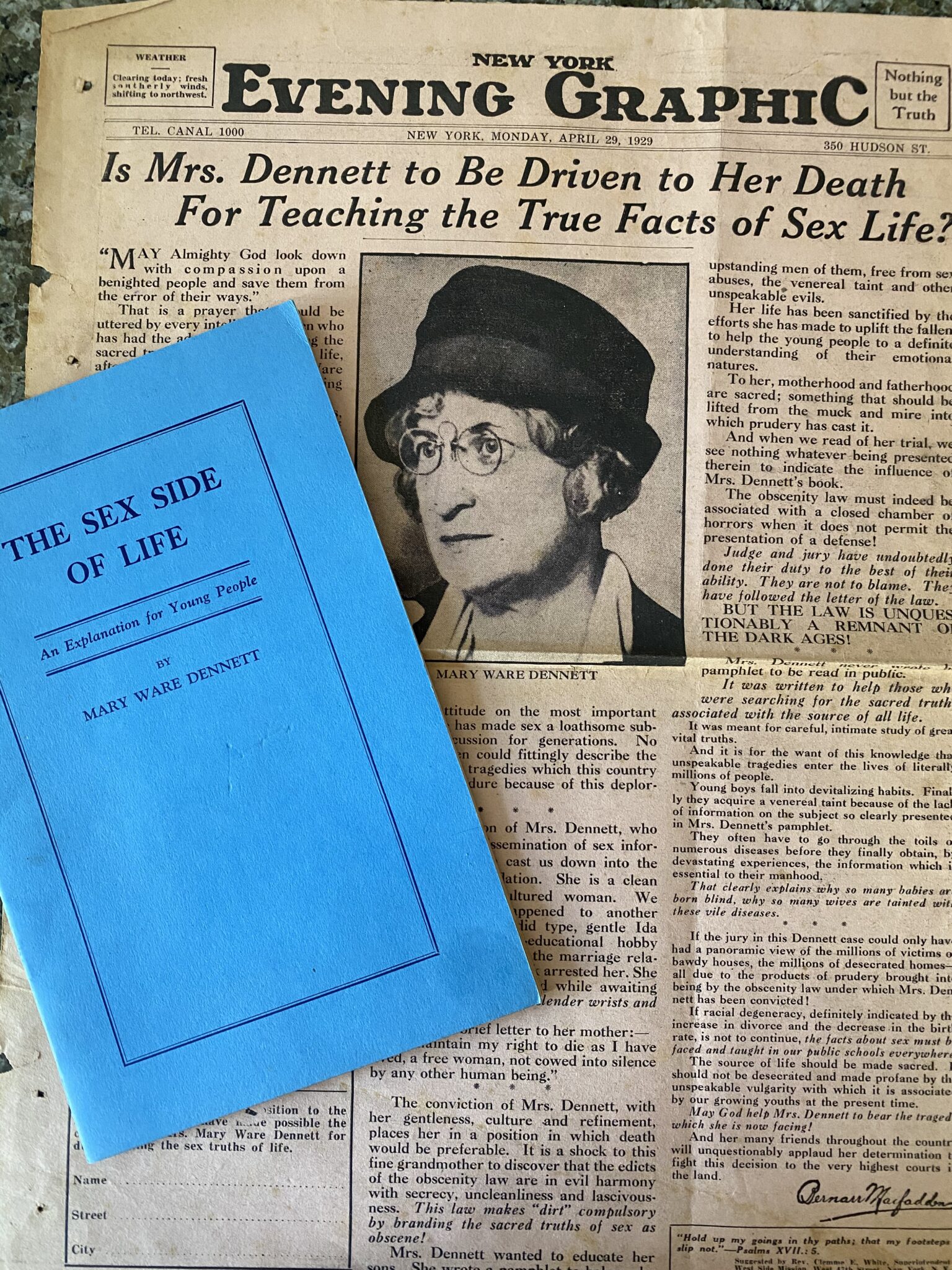

SOME WEEKS AGO, I came across a notice concerning the 1947 death of a woman named Mary Ware Dennett at a nursing home in Valatie.

As I have been reading about Mrs. Dennett this past year, I have learned of her historically-important contributions to birth control and sex education, issues still at the forefront of heated arguments across the country. But I also knew she advocated on these matters from her New England and New York City homes. So, how did she get to Valatie?

Mary Coffin Ware was born in Worchester, MA, in 1872.

She married Hartley Dennett, an architect, in 1900 and bore three children over the next five years. Her first son was born healthy; her second was born after a difficult labor and soon died; her third son was born in 1905. These pregnancies severely affected her health and she abandoned work as an artist and interior designer.

In 1907 Mary Ware Dennett had corrective surgery to repair birth-induced lacerations in her uterus. Advised against further pregnancy, and without the availability of contraception, she and her husband stopped having intercourse. Her husband soon started an affair with a close family friend and the Dennett marriage ended in short order.

In the aftermath of this betrayal, Mrs. Dennett started a new professional life as an organizer for women’s suffrage, birth control and sex education.

Speaking with The Columbia Paper recently, family archivist Sharon Spaulding, who is working on a biography based on newly discovered family letters, noted that Mrs. Dennett felt “obligated to work through existing structures to bring about change.”

Mrs. Dennett moved in 1910 to bohemian Greenwich Village, meeting regularly with other reform-minded women, and later to a small Murphy-bedded Manhattan apartment reflecting her modest temperament and marginal income. A skilled communicator, she served as correspondence secretary for the National American Women Suffrage Association until 1915 when she became president of the Twilight Sleep Association which she had co-founded a year earlier to advocate for anesthetizing pregnant women to alleviate childbirth pains.

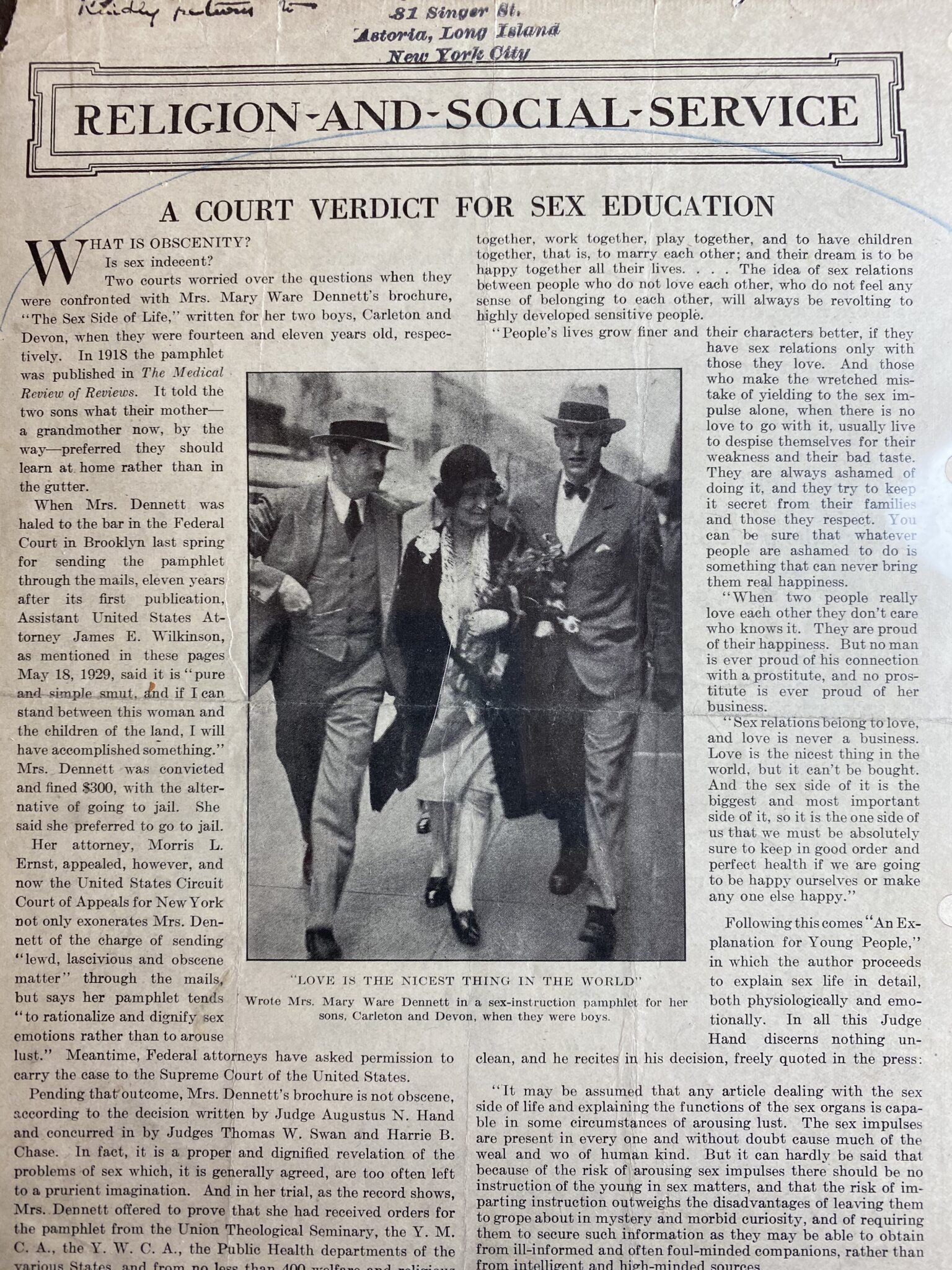

In 1915, Mrs. Dennett wrote a groundbreaking essay, “The Sex Side of Life: An Explanation for Young People,” for her young sons, who had begun asking her about sex. Originally published in a medical journal in 1918, doctors were impressed with the essay’s clear and specific language free of misleading or harmful information. One doctor told her it was the first publication he felt comfortable sharing with patients who asked him what they should say to their children asking them about sex.

Flooded with requests for a copy of the essay, Mrs. Dennett published “The Sex Side of Life” as a 21-page, illustrated pamphlet, selling for 25 cents, that she distributed to school, youth, religious, and health care groups. Through 30 printings, her family continued to send the pamphlet out until 1964.

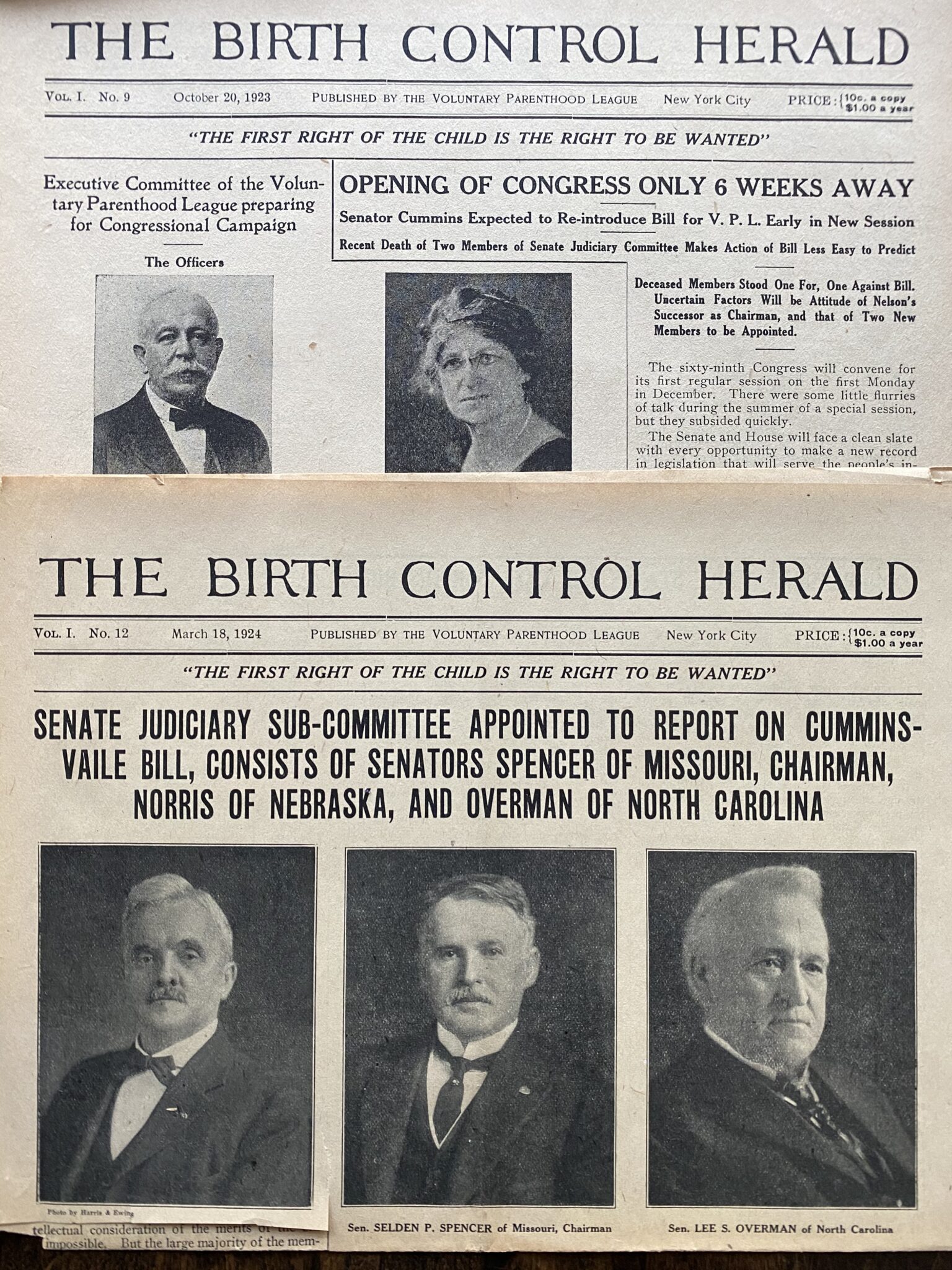

In 1915, too, Mrs. Dennett co-founded the National Birth Control League, the first American birth control organization.

In the mid-1920s, living on a meager income, Mrs. Dennett moved to Queens, where she initially lived alone while writing accounts of her birth control and anti-censorship struggles. In the late 1930s she started living with her third son Devon, his wife Marie, and their daughters Sally and Joanna.

In 1922, under the infamous Comstock Act, “The Sex Side of Life” was deemed “lewd, lascivious, and obscene.” Seven years later, Mrs. Dennett was indicted for using the U.S. mail to distribute her pamphlet. Represented by the civil libertarian attorney Morris Ernst, she was convicted, but refused to pay a fine. Her conviction was appealed and overturned in 1930.

Attorney Ernst and other lawyers soon used Mrs. Dennett’s case to counter Comstock Act obscenity bans on James Joyce’s “Ulysses” and works by other authors.

Describing her advocacy of educational and legislative reform, Mrs. Dennett wrote four books within a dozen years of activism concerning birth control and sex education, each praised for its comprehensiveness and practicality: “The Case for Birth Control” (1920); “Birth Control Laws: Shall We Keep Them, Change Them, or Abolish Them?” (1926); “Who’s Obscene?” (1930); “The Sex Education of Children: A Book for Parents” (1931).

In 1945, Mary Ware Dennett, suffering debilitating stroke-related symptoms, moved to Valatie, where her granddaughter Sally Dennett lived. She passed away on July 26, 1947, at the age of 75, at the now-named The Grand Rehabilitation and Nursing at Barnwell.

In 2020, Time magazine named her one of nine important women largely overlooked by history.

If the Marvelous Mrs. Maisel Met the Dynamic Mrs. Dennett—Sex Ed And Censorship Would Be So 20th Century

If the Marvelous Mrs. Maisel Met the Dynamic Mrs. Dennett—Sex Ed And Censorship Would Be So 20th Century

Published by Ms. Magazine, February 17, 2022

From 1915 through the 1930s, Mary Ware Dennett’s pioneering battles against U.S. government censorship helped pave the way for the freedom of speech Midge Maisel relies on and fights to expand.

Rachel Brosnahan as Midge Maisel. (Courtesy of Amazon Studios)

Like other fans of Amazon’s The Marvelous Mrs. Maisel, I’ll be binge-watching when the fourth season of the hit series finally drops on Friday, Feb. 18. There’s something deeply cathartic about watching the glamorous Midge Maisel battle sexism and censorship. Wielding words like poison stilettos, Maisel turns the narratives of everyday life into comedic shards that cut to the truth of self doubt, setback and triumph on the path to personal reinvention. We don’t need to be a 20-something, divorced mother of two in the late 1950s to relate to her experiences as a woman battling to be heard.

I can’t help but wonder if the fictional Midge Maisel was influenced by the real-life Mary Ware Dennett or what would happen if they met. It’s possible that at least some of Maisel’s pluck and fortitude was derived from learning about women like Dennett in newspapers and magazines. Dennett wasn’t a comedian, she was an activist. From 1915 through the 1930s, Dennett’s pioneering battles against the U.S. government’s censorship helped pave the way for the freedom of speech that Maisel both relies on and fights to expand.

Dennett was a chink in the armor of U.S. obscenity laws, a just-the-facts advocate for honesty in sex education. Unlike Maisel, who grew up in New York, Dennett was a transplant to Manhattan from Boston. That’s where their differences end, and the story of two fearless women pushing the boundaries of legal and cultural norms begins.

As young wives, Maisel and Dennett seemed to have it all—the man of their dreams, healthy children, up and coming lifestyles—everything they thought they desired. But each woman’s perfect world came crashing down—and for both, it was about sex. Maisel’s man left her for his secretary. For Dennett, difficulties in childbirth left her with a painful choice: risk death if she had another child, or abstain from sexual intercourse. Abstinence proved impossible for Dennett’s husband and in 1908, he scampered off to start a commune in New Hampshire.

Betrayed and humiliated, both women channeled their considerable creative energies into reinventing themselves. Maisel followed her penchant for wisecracks into a career as a standup comedian, initially doing gigs in back-alley clubs in Greenwich Village. Dennett joined the suffrage movement in Massachusetts, and was later recruited to the national headquarters in New York. Arriving in Manhattan in 1910, Dennett cut her hair and her corset, then she took a lover. Like Maisel, she found her tribe in the smoke-filled back rooms of the Village, but Dennett’s group called itself Heterodoxy, a secret sorority of feminist artists, writers and reformers.

“But wait. Back up,” Midge Maisel might say, pausing for effect and raising an eyebrow in suspicion. “Why would Mary Ware Dennett and her husband have to abstain from sex? Couldn’t they use condoms?”

Article published on May 19, 1930, in the Literary Digest. Mary Ware Dennett was an advocate for honesty in sex education. (Courtesy)

The answer is no. In 1873, Anthony Comstock, the anti-smut crusader and head of New York’s Suppression of Vice, succeeded in making all forms of birth control illegal after Congress passed his anti-obscenity statutes. Later known as the Comstock laws, these statutes even prohibited information about the prevention of conception by equating it with pornography. With the stroke of a pen, conversations about how to prevent pregnancy became illegal even between doctors and patients. Anyone found guilty could be fined up to $5,000 and sentenced to prison. Comstock himself once boasted that he’d been responsible for more than 4,000 arrests and the suicides of 15 “deviants.”

Maisel and her friend, Lenny Bruce, may be unaware, but their arrests and battles over censorship are directly related to the laws that Dennett sought to change. By 1915, then 43-year-old Dennett realized that winning the vote for women was only one prong on the path to equality. She quit her job at suffrage headquarters and co-founded the National Birth Control League, the first organization of its kind in the U.S. Its mission was to change the Comstock laws and transform cultural views about sex.

Although the country was beginning to wrestle with its notions about women and morality, the prevailing attitude still held that procreation, or securing the future of the species, was a woman’s supreme duty. The idea that women might regard sex as a creative, pleasurable and emotionally fulfilling act, was beyond their comprehension.

So strong were these social, religious and legal chokeholds on women, that even in the late 1950s, when Maisel reunites with her ex in an evening of passion, or when she falls into the arms of the dreamy doctor, she’s breaking accepted norms.

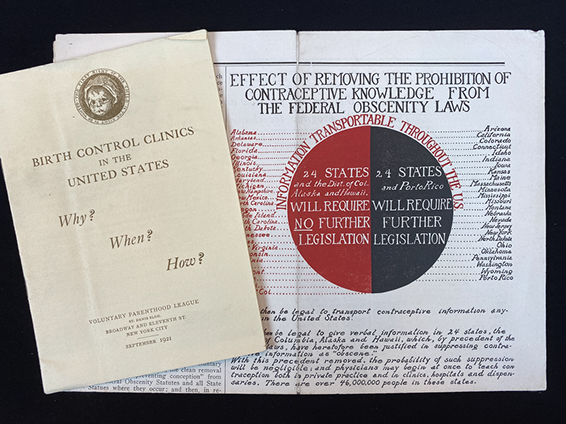

The offending educational pamphlet, written in 1915, sent to anyone requesting a copy until 1964—almost 20 years after Dennett’s death. (Courtesy)

Besides wanting to change public attitudes and the law, Dennett also wanted her teenage boys to learn the facts about sex rather than be tainted by Victorian myth and misconception. Scouring the libraries for suitable books to give them but finding none, she penned her own pamphlet called, The Sex Side of Life: An Explanation for Young People. If Maisel had seen the pamphlet, she might say, “Women will fix it and accessorize it!”

A former professor of art, Dennett illustrated it with anatomically correct drawings. Frontal and side-view diagrams of penises, vaginas and the entire reproductive system. Dennett shared her booklet with friends who shared it with friends and so on, until eventually, it found its way into the respectable Medical Review of Reviews, winning praise and endorsements. Struggling to earn money, she began selling the pamphlet to anyone who wrote to her with a request and a quarter.

About the same time, across the ocean in Switzerland, James Joyce began writing Ulysses, one of literature’s most groundbreaking novels. Its publication immediately became ensnared by censorship laws in Europe and the U.S. In an odd twist of fate, Dennett’s pamphlet and Joyce’s novel became inextricably linked—not unlike the interwoven careers of Midge Maisel and Lenny Bruce.

Fast forward to January 1929 at a federal courthouse in Brooklyn. Now a grandmother and retired from birth control work, Dennett was indicted and arrested for sending obscene material—her sex ed pamphlet—through the mail. The lead counsel of The American Civil Liberties Union, a close friend of Dennett’s, rose to her defense. Declaring her case to be on par with those of Copernicus and Darwin, he marshaled more than 30 experts in academia, religion and medicine to testify that contrary to being smut, Dennett’s book was scientific and educational.

The prosecuting attorney countered that “this woman” and her booklet “…opens the window … and beckons in all the neighbors’ children” to corrupt them. In overly dramatic tones that one reporter called a “caricature” of performance, the prosecutor read passages to the jury that were taken out of context. A Methodist pastor and professor of philosophy at Yale University who was present for the trial, called the prosecutor’s remarks “medieval fatheadism” and “hot air.”

Yet the prosecutor convinced the all-male jury that the booklet’s discussion of masturbation, its illustrations, its discussions of the possible delights of sexual union, would “lead our children not only into the gutter, but below the gutter and into the sewer.” And he attempted to strike a note of patriotic duty in finding Dennett guilty:

None of Dennett’s experts were allowed to testify and the jury took just 45 minutes to find her guilty of obscenity. Maisel would have noted, as did Dennett, that there weren’t any female faces among the jurors. “Her peers?” Maisel would have mocked. “You call this a jury of her peers?” raising another eyebrow. Women weren’t allowed to serve on federal juries until the passage of the Civil Rights Act in 1957.

It’s easy to imagine Dennett’s sense of utter defeat at the hands of what she called “obdurate” humans. She would have agreed with Maisel’s dad, Abe, when he laments aloud on the subway, “The greatest threat to humanity is ignorance.”

Dennett’s legal dream team immediately filed an appeal. By this time, public, if not political, attitudes had shifted. The nation was riveted by the trial and like Maisel, Dennett gained something of a cult following. Fundraisers were held, letter writing campaigns were launched, and petitions were sent to then President Hoover. When the press repeatedly described Dennett as a “silver-haired,” grandmotherly type, continually using an unflattering picture, Dennett did what Maisel would have done: She got proactive. Dennett started sending reporters photos that were more flattering along with a copy of her resume that touted an accomplished career.

Mary Ware Dennett, circa 1893. (Courtesy)

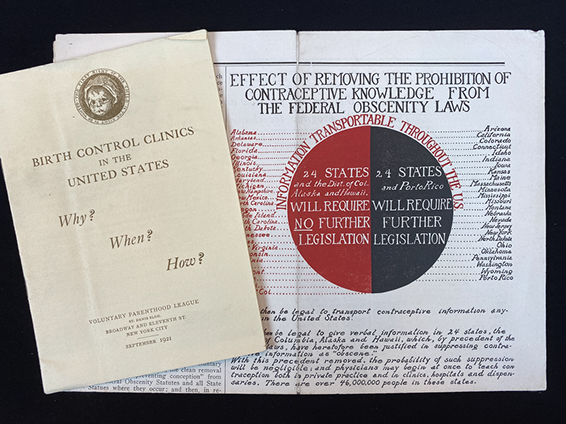

The Birth Control Herald, published by the Voluntary Parenthood League, founded by Mary Ware Dennett. (Courtesy)

During the months that followed her conviction and the appellate court’s ruling, a reporter for the New York Telegram uncovered the truth behind the trial. The entire thing had been a sham, a government sting operation as payback for Dennett’s work to change the laws. In an act that Maisel would have declared pure “Comstockery,” a postal inspector named C.E. Dunbar had written to Dennett under the fictitious name of Mrs. Carl A. Miles to request a copy of The Sex Side of Life. Dunbar had even ordered stationery printed with the fictitious woman’s name and address. Dennett, as she always did, mailed the requested copy, thereby setting in motion her indictment, arrest and trial.

Maisel may be famous for her brisket, but I laugh to think of the mincemeat she’d make of Mr. C.E. Dunbar.

Almost one year later, in March 1930, the appellate court reversed Dennett’s conviction, setting one of the most important legal precedents of the 20th century. While it wasn’t the victory Dennett had fought to achieve, nevertheless, it created a fracture in the laws that had held captive both reproductive rights and the legal definition of obscenity for nearly 60 years.

Three years later, Dennett’s attorney was back in court, battling censorship laws, this time on behalf of Random House and its right to publish Joyce’s Ulysses. Citing Dennett’s precedent-setting legal victory, the court ruled in favor of its publication along with other previously banned books in the U.S.

As for Dennett, when the Great Depression settled in, her fame receded into the shadows. At the time of her death in 1947, 23 editions published of The Sex Side of Life and it had been translated into 15 languages. Her family continued to sell it until 1964. I own a stack of yellowed copies of the pamphlet and am struck by its straightforward, common sense approach to sex education—still a rarity today. I can imagine an episode of the Marvelous Mrs. Maisel that begins with Maisel dropping a quarter into an envelope and mailing it to Dennett.

Receiving her requested copy, Maisel might respond as she quipped in one episode, “If you have underwear on, you’re overdressed.”

The Sex Education Pamphlet That Sparked a Landmark Censorship Case

The Sex Education Pamphlet That Sparked a Landmark Censorship Case

Published by Smithsonian, September 30, 2021

It only took 42 minutes for an all-male jury to convict Mary Ware Dennett. Her crime? Sending a sex education pamphlet through the mail.

Charged with violating the Comstock Act of 1873—one of a series of so-called chastity laws—Dennett, a reproductive rights activist, had written and illustrated the booklet in question for her own teenage sons, as well as for parents around the country looking for a new way to teach their children about sex.

Lawyer Morris Ernst filed an appeal, setting in motion a federal court case that signaled the beginning of the end of the country’s obscenity laws. The pair’s victory marked the zenith of Dennett’s life work, building on her previous efforts to publicize and increase access to contraception and sex education. (Prior to the trial, she was best known as the more conservative rival of Margaret Sanger, founder of Planned Parenthood.) Today, however, United States v. Dennett and its defendant are relatively unknown.

“One of the reasons the Dennett case hasn’t gotten the attention that it deserves is simply because it was an incremental victory, but one that took the crucial first step,” says Laura Weinrib, a constitutional historian and law scholar at Harvard University. “First steps are often overlooked. We tend to look at the culmination and miss the progression that got us there.”

Dennett wrote the pamphlet in question, The Sex Side of Life: An Explanation for Young People, in 1915. Illustrated with anatomically correct drawings, it provided factual information, offered a discussion of human physiology and celebrated sex as a natural human act.

“[G]ive them the facts,” noted Dennett in the text, “... but also give them some conception of sex life as a vivifying joy, as a vital art, as a thing to be studied and developed with reverence for its big meaning, with understanding of its far-reaching reactions, psychologically and spiritually.”

After Dennett’s 14-year-old son approved the booklet, she circulated it among friends who, in turn, shared it with others. Eventually, The Sex Side of Life landed on the desk of editor Victor Robinson, who published it in his Medical Review of Reviewsin 1918. Calling the pamphlet “a splendid contribution,” Robinson added, “We know nothing that equals Mrs. Dennett’s brochure.” Dennett, for her part, received so many requests for copies that she had the booklet reprinted and began selling it for a quarter to anyone who wrote to her asking for one.

These transactions flew in the face of the Comstock Laws, federal and local anti-obscenity legislation that equated birth control with pornography and rendered all devices and information for the prevention of conception illegal. Doctors couldn’t discuss contraception with their patients, nor could parents discuss it with their children.

The Sex Side of Life offered no actionable advice regarding birth control. As Dennett acknowledged in the brochure, “At present, unfortunately, it is against the law to give people information as to how to manage their sex relations so that no baby will be created.” But the Comstock Act also stated that any printed material deemed “obscene, lewd or lascivious”—labels that could be applied to the illustrated pamphlet—was “non-mailable.” First-time offenders faced up to five years in prison or a maximum fine of $5,000.

In the same year that Dennett first wrote the brochure, she co-founded the National Birth Control League (NBCL), the first organization of its kind. The group’s goal was to change obscenity laws at a state level and unshackle the subject of sex from Victorian morality and misinformation.

By 1919, Dennett had adopted a new approach to the fight for women’s rights. A former secretary for state and national suffrage associations, she borrowed a page from the suffrage movement, tackling the issue on the federal level rather than state-by-state. She resigned from the NBCL and founded the Voluntary Parenthood League, whose mission was to pass legislation in Congress that would remove the words “preventing conception” from federal statutes, thereby uncoupling birth control from pornography.

Dennett soon found that the topic of sex education and contraception was too controversial for elected officials. Her lobbying efforts proved unsuccessful, so in 1921, she again changed tactics. Though the Comstock Laws prohibited the dissemination of obscene materials through the mail, they granted the postmaster general the power to determine what constituted obscenity. Dennett reasoned that if the Post Office lifted its ban on birth control materials, activists would win a partial victory and be able to offer widespread access to information.

Postmaster General William Hays, who had publicly stated that the Post Office should not function as a censorship organization, emerged as a potential ally. But Hays resigned his post in January 1922 without taking action. (Ironically, Hays later established what became known as the Hays Code, a set of self-imposed restrictions on profanity, sex and morality in the motion picture industry.) Dennett had hoped that the incoming postmaster general, Hubert Work, would fulfill his predecessor’s commitments. Instead, one of Work’s first official actions was to order copies of the Comstock Laws prominently displayed in every post office across America. He then declared The Sex Side of Life “unmailable” and “indecent.”

Undaunted, Dennett redoubled her lobbying efforts in Congress and began pushing to have the postal ban on her booklet removed. She wrote to Work, pressing him to identify which section was obscene, but no response ever arrived. Dennett also asked Arthur Hays, chief counsel of the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU), to challenge the ban in court. In letters preserved at Radcliffe College’s Schlesinger Library, Dennett argued that her booklet provided scientific and factual information. Though sympathetic, Hays declined, believing that the ACLU couldn’t win the case.

By 1925, Dennett—discouraged, broke and in poor health—had conceded defeat regarding her legislative efforts and semi-retired. But she couldn’t let the issue go entirely. She continued to mail The Sex Side of Life to those who requested copies and, in 1926, published a book titled Birth Control Laws: Shall We Keep Them, Change Them, or Abolish Them?

Publicly, Dennett’s mission was to make information about birth control legal; privately, however, her motivation was to protect other women from the physical and emotional suffering she had endured.

The activist wed in 1900 and gave birth to three children, two of whom survived, within five years. Although the specifics of her medical condition are unknown, she likely suffered from lacerations of the uterus or fistulas, which are sometimes caused by childbirth and can be life-threatening if one becomes pregnant again.

Without access to contraceptives, Dennett faced a terrible choice: refrain from sexual intercourse or risk death if she conceived. Within two years, her husband had left her for another woman.

Dennett obtained custody of her children, but her abandonment and lack of access to birth control continued to haunt her. Eventually, these experiences led her to conclude that winning the vote was only one step on the path to equality. Women, she believed, deserved more.

In 1928, Dennett again reached out to the ACLU, this time to lawyer Ernst, who agreed to challenge the postal ban on the Sex Side of Life in court. Dennett understood the risks and possible consequences to her reputation and privacy, but she declared herself ready to “take the gamble and be game.” As she knew from press coverage of her separation and divorce, newspaper headlines and stories could be sensational, even salacious. (The story was considered scandalous because Dennett’s husband wanted to leave her to form a commune with another family.)

Dennett cofounded the National Birth Control League, the first organization of its kind in the U.S., in 1915. Three years later, she launched the Voluntary Parenthood League, which lobbied Congress to change federal obscenity laws. Sharon Spaulding / Dennett Family Archive

“Dennett believed that anyone who needed contraception should get it without undue burden or expense, without moralizing or gatekeeping by the medical establishment,” says Stephanie Gorton, author of Citizen Reporters: S.S. McClure, Ida Tarbell and the Magazine That Rewrote America. “Though she wasn't fond of publicity, she was willing to endure a federal obscenity trial so the next generation could have accurate sex education—and learn the facts of life without connecting them with shame or disgust.”

In January 1929, before Ernst had finalized his legal strategy, Dennett was indicted by the government. Almost overnight, the trial became national news, buoyed by The Sex Side of Life’s earlier endorsement by medical organizations, parents’ groups, colleges and churches. The case accomplished a significant piece of what Dennett had worked 15 years to achieve: Sex, censorship and reproductive rights were being debated across America.

During the trial, assistant U.S. attorney James E. Wilkinson called the Sex Side of Life “pure and simple smut.” Pointing at Dennett, he warned that she would “lead our children not only into the gutter, but below the gutter and into the sewer.”

None of Dennett’s expert witnesses were allowed to testify. The all-male jury took just 45 minutes to convict. Ernst filed an appeal.

In May, following Dennett’s conviction but prior to the appellate court’s ruling, an investigative reporter for the New York Telegram uncovered the source of the indictment. A postal inspector named C.E. Dunbar had been “ordered” to investigate a complaint about the pamphlet filed by an official with the Daughters of the American Revolution (DAR). Using the pseudonym Mrs. Carl Miles, Dunbar sent a decoy letter to Dennett requesting a copy of the pamphlet. Unsuspecting, Dennett mailed the copy, thereby setting in motion her indictment, arrest and trial. (Writing about the trial later, Dennett noted that the DAR official who allegedly made the complaint was never called as a witness or identified. The activist speculated, “Is she, perhaps, as mythical as Mrs. Miles?”)

Dennett’s is a name that deserves to be known.

When news of the undercover operation broke, Dennett wrote to her family that “support for the case is rolling up till it looks like a mountain range.” Leaders from the academic, religious, social and political sectors formed a national committee to raise money and awareness in support of Dennett; her name became synonymous with free speech and sex education.

In March 1930, an appellate court reversed Dennett’s conviction, setting a landmark precedent. It wasn’t the full victory Dennett had devoted much of her life to achieving, but it cracked the legal armor of censorship.

“Even though Mary Ware Dennett wasn’t a lawyer, she became an expert in obscenity law,” says constitutional historian Weinrib. “U.S. v. Dennett was influential in that it generated both public enthusiasm and money for the anti-censorship movement. It also had a tangible effect on the ACLU’s organizational policies, and it led the ACLU to enter the fight against all forms of what we call morality-based censorship.”

Ernst was back in court the following year. Citing U.S. v. Dennett, he won two lawsuits on behalf of British sex educator Marie Stopes and her previously banned books, Married Love and Contraception. Then, in 1933, Ernst expanded on arguments made in the Dennett case to encompass literature and the arts. He challenged the government’s ban on James Joyce’s Ulysses and won, in part because of the precedent set by Dennett’s case. Other important legal victories followed, each successively loosening the legal definition of obscenity. But it was only in 1970 that the Comstock Laws were fully struck down.

Ninety-two years after Dennett’s arrest, titles dealing with sex continue to top the list of the American Library Association’s most frequently challenged books. Sex education hasn’t fared much better. As of September 2021, only 18 states require sex education to be medically accurate, and only 30 states mandate sex education at all. The U.S. has one of the highest teen pregnancy rates of all developed nations.

What might Dennett think or do if she were alive today? Lauren MacIvor Thompson, a historian of early 20th-century women’s rights and public health at Kennesaw State University, takes the long view:

While it’s disheartening that we are fighting the same battles over sex and sex education today, I think that if Dennett were still alive, she’d be fighting with school boards to include medically and scientifically accurate, inclusive, and appropriate information in schools. ... She’d [also] be fighting to ensure fair contraceptive and abortion access, knowing that the three pillars of education, access and necessary medical care all go hand in hand.

At the time of Dennett’s death in 1947, The Sex Side of Life had been translated into 15 languages and printed in 23 editions. Until 1964, the activist’s family continued to mail the pamphlet to anyone who requested a copy.

“As a lodestar in the history of marginalized Americans claiming bodily autonomy and exercising their right to free speech in a cultural moment hostile to both principles,” says Gorton, “Dennett’s is a name that deserves to be known.”

Sharon Spaulding is a historian and researcher who specializes in the life and times of Mary Ware Dennett. The official curator of the Mary Ware Dennett family archives, Spaulding is at work on a book about Dennett’s court trial. She publishes the monthly newsletter “Women Make History: Stories We Should Have Learned in School” at sharonspaulding.com.

Mary Ware Dennett’s Rescued History

Mary Ware Dennett’s Rescued History

Published by New Hampshire Magazine, February 18, 2021

There’s an emotional angst and urgency swirling in my soul. It’s a nagging sense of obligation and a question every time I look under my bed or open my basement closets: “To toss or not to toss?”

Apologies, Marie Kondo, but let’s not all rush to tidy up

There’s an emotional angst and urgency swirling in my soul — and it’s not directly related to COVID-19. It’s a nagging sense of obligation and a question every time I look under my bed or open my basement closets: “To toss or not to toss?”

Until Marie Kondo, the tidying guru, came along, those unorganized piles didn’t tug at my conscience. Maybe I’m just getting older and don’t want to leave my kids a house filled with stuff they don’t want. Or perhaps it’s hard to say goodbye to the memories that are stuffed inside the boxes in my closets. But while I’m all for what Marie calls “sparking joy,” I’ve also learned that, sometimes, procrastination is the better path.

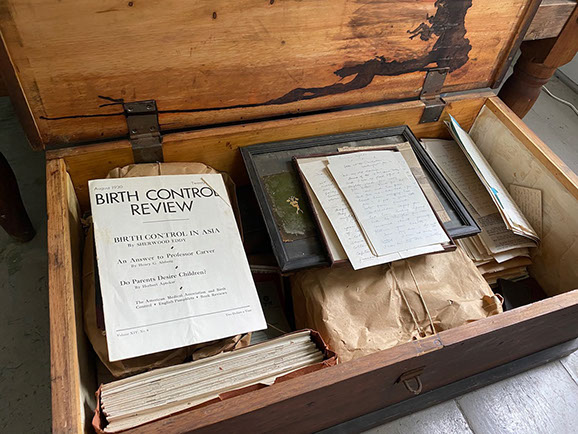

Sharon Spaulding discovered a trunk of papers belonging to equal rights advocate Mary Ware Dennett at her family’s summer home in Alstead. Courtesy photo

Often, mundane objects are the ones I cherish the most. Tattered photographs can instantly conjure a memory, a smile, a sound, bringing something — or someone — to life. Those scrawled love notes from my then-4-year-old trace not only the archeology of our existence, but also the human heart.

Have you ever thrown something out, then regretted it?

When my mom died, I became Ms. Efficiency on steroids. Her clothes were either tossed or donated. Months later, after my best friend died, her kids transformed her clothes into cozy lap quilts. I regretted my haste with my mother’s things. When my father passed, I grabbed his well-worn, red-and-black flannel shirt. Although it looks out of place hanging in my closet filled

with mostly Ann Taylor-style clothing, simply seeing that shirt each day evokes the smell of my father’s aftershave and warm memories of him wrapping me in his arms.

On a recent evening, two of my three adult children and I cleaned out a chest of drawers in an old house in Alstead, New Hampshire, that has been in my husband’s family for more than 100 years. We’ve spent every summer here since they were babies. As children, they’d run wild and barefoot in its fields of clover, Queen Anne’s Lace and milkweed. Together, we’d rise at 2 a.m. to watch meteor showers streak across the sky like fireflies, and play weeklong games of Scrabble, Canasta and Monopoly.

This same old house had steamer trunks in the attic that taunted me for years, trunks filled with letters, papers and journals dating to 1848. As my husband and I continued the tradition of annual visits, I began to leave my summer reading at home in favor of digging into those trunks. What I discovered was the life story of an extraordinary woman, one who brought about some of the most significant changes in equal rights in the early 20th century, and then was quickly forgotten. Although chances are slim that you’ve heard her name, that woman, Mary Ware Dennett, was recently celebrated by Time magazine as one of nine women in American history that everyone should know.

The attic where Spaulding found Mary Ware Dennett’s journals and papers dating back to 1848. Courtesy photo

Dennett was a reproductive rights advocate, an artist, the second-in-command of the National American Woman Suffrage Association, a pacifist, and an outspoken defender of Black women’s rights. She was a contemporary and bitter rival of Margaret Sanger because Dennett was devoted to making the world better for all, not just a few. Like her relative, Lucretia Coffin Mott, who teamed up with Elizabeth Cady Stanton to launch the women’s movement at Seneca Falls in 1848, Dennett’s aim was nothing less than fulfilling the original promises of the Declaration of Independence.

The attic where Spaulding found Mary Ware Dennett’s journals and papers dating back to 1848. Courtesy photo

At the 1913 women’s march on Washington, D.C., intended to upstage the inauguration of anti-suffragist Woodrow Wilson, it was Dennett who reprimanded parade organizer Alice Paul for discriminating against Black suffragists.

“The Suffrage movement stands for enfranchising every single woman in the United States and there [is] no occasion when we would be justified in not living up to our principles,” Dennett said. And in a second rebuke, she said, “All colored women who wish to march shall be accorded every service given to other marchers.”

Believing the “first right of every child is to be wanted,” it was Dennett, not Sanger, who in 1915 started the first national birth control organization in the U.S.

It was also Dennett who battled the U.S. government in a landmark case over sex education and censorship. Her victory in 1930 soon after enabled publication of previously banned books such as James Joyce’s “Ulysses.” A pacifist, there is even evidence that Dennett co-founded what later became the American Civil Liberties Union.

At the end of her long career, in the 1940s, Dennett offered her extensive files to the library at Harvard. These chronicled women’s suffrage from 1908-1915, the battle for reproductive rights from 1915-1930s, the founding of the Women’s Peace Party and the World Federalist Society prior to World Wars I and II, plus her work on First Amendment issues. Silly girl. Harvard, that all-male bastion of elite education, declined and this precious record of history ended up in my family’s attic.

Eventually, in the late 1980s, my mother-in-law donated most of the papers to the Schlesinger Library at Radcliffe College, but not Dennett’s private journals, those that chronicle her hopes and fears, her struggles to rise again and again in the face of public ridicule. These papers now form the basis of a book I’m writing about her life.

Dennett advocated for, among other things, women’s right to vote and reproductive freedom. Courtesy photo

Imagine if a Marie Kondo-style cleaning had been done and the trunks unceremoniously dumped. Her voice would have been forever silenced. We would have missed the unfolding of her life not only through her words, but also in the mementos she saved — a scrap of material for a new dress, a favorite poem, a ticket stub from a symphony. Across the centuries, these and other trinkets resurrect a fully living, breathing woman, not merely a list of accomplishments.

Amid the most mundane chatter about the clothes that needed mending, the weather, or the pesky gray hairs that were emerging about her face, are references to the deep disappointments of a failed argument in Congress or the humiliation of lies promulgated by her opposition in the press. It all makes Dennett’s voice more approachable and relevant to the battles we’re still fighting today.

Had her children rushed to tidy up when she died and tossed the remnants of her life, none of us would know her name, her story. None of us would know on whose shoulders we stand or discover from her just how she managed to juggle the many hats she wore. I’m learning more from Mary Ware Dennett today than I could ever have imagined. It’s why I now sort my piles with less haste.

Find Out More

Sharon Spaulding has spent 10 years researching the life of suffragist and sex-ed activist Mary Ware Dennett. She is working on a book about Dennett’s life, and also publishes a monthly newsletter, “Women Make History: Stories We Should Have Learned in School.”

Why A Pro Never Does Her Own Promo

Why A Pro Never Does Her Own Promo

Published by San Francisco Writers Conference, July 21, 2021

Marketing pro Sharon Spaulding has promoted tech startups, authors, international nonprofits, Fortune 50 companies and celebrities. But when it came to promoting herself—establishing her author brand, building a platform, and cultivating a devoted following of readers—she was flummoxed.

“I’m very good at what I do but cannot do it for myself,” Sharon says. “I was so immersed in my book project that I wasn’t a good judge of what opportunities I should pursue to build my brand and platform.”

One year after attending the 2020 SFWC, Sharon has a recognized brand, a national platform, and a growing following. Her secret: Despite her expertise, Sharon didn’t hesitate to hire professionals and follow their advice. As Steven Pressfield writes in the War of Art: Break Through the Blocks and Win Your Creative Battles: “A professional recognizes her limitations. She gets an agent, she gets a lawyer, she gets an accountant. She knows she can only be professional at one thing. She brings in other pros and treats them with respect.”

To Brand or Not To Brand

It’s not unusual for writers to be intimidated by the business side of being an author. I’m a book coach—the pro Sharon hired—and when I coach authors-to-be, I distill terms like “brand” to their essence: A brand creates buzz. Or as Jeff Bezos once said: “A brand is what other people say about you when you’re not in the room.”

I also love literary agent Liz Parker’s perspective: “Platform is the number of people who know you. Your network is the number of people you know.”

Sharon wanted a platform that would boost her own writing career while also giving Mary Ware Dennett, the subject of Sharon’s novel-in-progress, her rightful place in American history.

“I’m writing historical fiction that explores Mary’s roles as suffragist, sex education activist and reproductive rights activist,” Sharon says. “Time magazine named Dennett one of the most important women in US history. Her groundbreaking court trial on obscenity charges paved the way for the publication of James Joyce’s Ulysses and yet few people have heard of Mary.”

Sharon shared Mary’s story with me during an Ask a Pro session at the 2020 SFWC. Since she’s a marketing pro and Ask a Pro is an opportunity for writers to obtain free advice, I immediately tossed out several DIY publicity ideas that would quickly boost her profile and platform.

“The consultation validated my gut sense that I needed to work with someone else,” says Sharon who traveled from her home in Utah to attend SFWC. “Every conference session I attended was relevant to my process. SFWC more than delivers on its promise.”

Women Make History

After Sharon hired me, I redesigned her website; rebranded her as Sharon Spaulding, feminist historian; edited her pitch and logline; developed social media platforms; edited her book manuscript; and helped her create pitches for essays and articles that have caught the attention of national magazine editors. Sharon was featured in a two-page spread in New Hampshire magazine and has an essay forthcoming in Ms. Magazine, among others. She was also featured on Dr. Buzzkill, a popular podcast for history nerds, in an episode that received more than 1,000 downloads in the first 30 minutes.

Together we designed and launched Sharon’s free monthly newsletter, Women Make History, featuring compact biographies of “women we should have learned about in school.” As expected, the newsletter’s Instagram ads have attracted new subscribers. But nothing has been as exhilarating as the word-of-mouth boosts when delighted subscribers share the newsletter with their circle of friends. Every month after the newsletter goes out, Sharon receives a tsunami of compliments—and more subscribers. Her recent campaign to have Mary Ware Dennett included in the national Women’s History Museum has gained traction as has her new campaign to have Mary’s image on a quarter. Best of all, agents are interested in her manuscript—and so are television producers.

Enjoy Life—Eat Pie

Enjoy Life—Eat Pie

Published by Utah Stories, April 7, 2017

Amble into the Sunglow Café in Bicknell (pop. 322), and you’ll think you’ve walked onto a movie set and into a world both familiar, but different.

At the Sunglow Cafe, you are likely to be welcomed and waited on by Saidee (left) or her mom, Misty (center), while Saidee’s dad, Brian, serves as manager and cook. Photos by Sharon Spaulding.

Mustard colored walls echo the sandstone outside. Large, teal painted arrows on the walls are reminiscent of ancient Native American symbols seeming to guide you on the path to wisdom. Inside this modern day Kiva a few miles outside of Torrey, these arrows point to a different sort of mantra written just inside the front door: Enjoy life. Eat Pie.

Though baseball caps have replaced cowboy hats, Levis still seem to fit just right over the mostly long, lean frames of men who sit as comfortably in a saddle as they do in an easy chair. Chances are you’ll be welcomed by Sadiee or her mom, Misty. Brian, Sadiee’s dad and Sunglow’s cook, flips burgers, eggs, and pancakes on the griddle.

At the Sunglow Café you can order steak and eggs for breakfast, steak and salad for lunch, or steak and potatoes for dinner. Bicknell is still cattle country. For $1.99, you can have chocolate milk. The menu is as long and deep as the famous red rock canyons nearby. But while people come in for good food at honest prices, curiosity seekers come to taste the fruit of knowledge: the Pickle and Pinto Bean pies.

Yes, you read correctly, the Pickle and Pinto Bean pies have made the Sunglow somewhat famous. They were the creation of Cula Ekker, who was once known as the “Pie Queen” of Wayne County.

No one knows the exact origin of Cula’s creations, but, says Brian, they date to the Depression when people simply had to make do with what they had and everything was made from scratch.

Cula’s brother, Milton Taft, says he and his sister were two of six siblings who grew up nearby on a farm. When Cula was just nine years-old, a brother was injured in a riding accident and spent most of a year in a hospital in Salt Lake City. Their mom went with him, leaving Cula to handle the cooking for the family and the farm hands.

“Cula loved to cook,” says Milton. “She was always cooking. She had a job for several years cooking at the local school.”

When Milton built the Sunglow motel in 1965, along with the restaurant, Cula signed on as chef and began serving up her famous Pickle Pie.

At the Sunglow Cafe, mustard colored walls echo the sandstone outside, while teal painted arrows reminiscent of Native American symbols point to a mantra the locals know so well. famous Pickle Pie.

According to Brian, legend has it that one day two bikers were passing through and one had a recipe for Pinto Bean pie. He and Cula swapped their secret formulas. No one knows what became of the biker, but Cula added the pinto bean to her menu.

Cula passed away a few years ago, but not before sharing her recipes with Bessie Stewart, who has worked at the Sunglow for 31 years. Also born and raised in Wayne County, Bessie comes in at 5 a.m. to make up about 14 fresh pies, and she still makes the soup noodles from scratch. Last November, she baked over 300 pies to fill Thanksgiving orders.

“Cooking is all I ever done all my life,” she says. “We moved to Hanksville when Lake Powell went in, and worked for people in motels and gas stations and then moved to Bicknell. I started working for Cula in 1983.”

In addition to continuing Cula’s legacy, Bessie is locally and affectionately known as the “pistol-packing pastry chef.” She once unloaded the barrel of a .22, firing at her husband as he tried to disappear into the darkness of a desert night.

At the Sunglow Cafe, mustard colored walls echo the sandstone outside, while teal painted arrows reminiscent of Native American symbols point to a mantra the locals know so well.

“The Lord was with him,” she laughs. “We were both so angry. When I picked up that gun, he knew I meant business and took off running. It was so dark I couldn’t see, so I fired at the sounds he made as he ran. It took a few years before we could laugh about it,” she says, “but eventually we made up.” Today, she has four kids, 15 grandchildren, and 15 great-grandchildren. Her husband passed away several years ago.

Says Brian, “Every summer we get about 50 tour buses packed with Europeans headed to Escalante. The French love the pies. We hear it over and over again that this is the type of pastry you would find in a different kind of eating establishment.”

What’s the secret? Says Bessie, “It’s the lard. We only use pure pork lard. It makes for the flakiest crust.”

In addition to Pickle and Pinto Bean, the Sunglow serves up Buttermilk and Oatmeal pies along with the more traditional Apple, Pecan, and Blueberry. Whole pies are $9.95 and a single slice is $3.49.

Pickle Pie has a sweet but tangy taste you might savor on a summer’s day, while the Pinto Bean, coconut mashed with the beans, has a hearty, stick-to-your-ribs kind of pie.

Whoever painted those four words on the wall was truly wise: Enjoy Life. Eat Pie. At least at the Sunglow Café.

Cula Ekker’s Pie Dough Recipe

6 cups sifted flour

2 teaspoons salt

1 – ¼ pounds (2-1/3 cups) of pure pork lard – no substitutions

12 tablespoons Water

2 tablespoons vinegar

2 eggs

Directions

In a mixing bowl, sift flour and salt. With pastry blender or two knives, cut in lard until mixture resembles coarse crumbs. Whisk together water, vinegar, and eggs until thoroughly mixed. Sprinkle liquid, 1 tablespoon at a time, into flour mixture, stirring lightly with a fork after each addition until the pastry is just moist enough to hold together. Shape pastry into a ball. Roll out as desired.

Like Mother Like Daughter: Helping Others Lift Themselves Out of Poverty

Like Mother Like Daughter: Helping Others Lift Themselves Out of Poverty

Published by BOLD, May 7, 2016

Growing up in Puerto Rico with 12 people in a three-room hut with an outhouse, Leah Barker never imagined that one day she would lead an international nonprofit working to lift families like hers out of poverty.

Fast forward to Salt Lake City where Barker, 50, runs an innovative $5 million organization working in rural areas in developing countries.

“I’ve lived it,” says Barker, from her industrial park office. “I watched my mom do it, and I’ve done it. Now I have the privilege of working with others, particularly women, to learn the skills they need to realize their own dreams and break the cycle of poverty.”

Dressed in khakis, T-shirt, and a scarf made by a women’s cooperative in one of “her” villages, Barker credits her success to her mom’s tenacity and being a great role model.

“My parents divorced when I was 5, and my dad never provided any support,” she said. “With my mom running the show, I knew I was headed somewhere, I just didn’t know where.

“My mom’s mantra was education. She used to tell us that the only need we had was getting an education. ‘If you need shoes,’ she would say, ‘it better be that the school requires them. If you don’t need shoes for school, you don’t need them.”

When her parents split up, her mother took a factory job earning just $500 per month to provide for a family of six. She also went back to school. She finished her high school diploma, got a bachelor’s degree, then a master’s, and finally became an elementary school teacher. “By the time I was in the third grade, she was my English teacher, ” says Barker.

After her own high school graduation, Barker followed in her mother’s footsteps and enrolled at the University of Puerto Rico, but also like her mother, she ended up marrying a “bozo,” as she refers to her first husband. Along the way, she moved to Utah where she dropped out of school to work to pay for his college education and take care of their two children.

“Eventually,” she recalls, “we separated. My mom’s advice? Get back into school.”

Barker listened to her mom and earned both a bachelor’s and a master’s degree. Her first job after college was with the Salt Lake County Housing Authority.

“When I went to the interview, the woman asked why she should hire me instead of the 60 other candidates who were much more qualified. Because, I told her, I’ve lived it. I watched my mother move us out of poverty, and now I’ve done it.” Barker got the job.

After a few years in that position and later with an educational nonprofit, in 2009, Barker became CEO of CHOICE Humanitarian, an international nonprofit working in rural areas of eight developing countries.

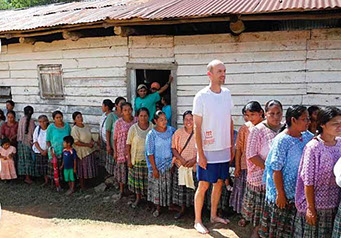

According to Barker, the CHOICE Leadership Model of village development focuses on empowering women to create their own path out of poverty. It is an integrated approach incorporating education, health, environment, culture and economic development. It is designed to strengthen local leadership and train others to become leaders.

“Of course, we also work with men and families,” Barker says, “but when you focus on the women, results happen. The moms are the ones who set the examples and raise the standards for their children.”

Since taking over as CEO, Barker has increased donations each year by $750,000.

“Every dollar donated to CHOICE is leveraged by a multiplier of five, and the organization is debt-free,” she says. “We practice what we teach.”

Her approach to fundraising is similar to the methodology CHOICE uses in villages.

“The point of our work,” she says, “is for villages to become self-sustaining and self-developing. The same is true for CHOICE as an organization.”

Barker is referring to an innovative approach to fundraising. Traditionally, nonprofits rely on the generosity of individual donors and grants. While CHOICE utilizes this approach, it also engages with corporations in two ways: one, they take company employees into the field to spend a week working alongside villagers on projects that the locals have determined to be critical to their path of self-reliance. Projects might include digging wells, building schools, health clinics, or even cook stoves.

The second approach with its corporate partners is one that helps to establish markets for products made in the villages. A leader in essential oils, doTERRA, funds CHOICE’S work to train small farmers in sustainable agricultural practices. The small farmers, in turn, grow environmentally green crops that are then sold to doTERRA at fair-market value.

“This provides economic opportunity for the villagers, and is helping CHOICE become a self-sustaining nonprofit,” Barker says. “Everyone wins.”

According to Barker, taking people into the field on expeditions is a life-changing experience. “You get to experience true partnership with others.

You find it isn’t about us helping them. It is about people helping people. That’s why we run expeditions for college students, families, even singles groups. As my mom used to say, we are all in this together.”

For companies, going on an expedition also creates team bonding across all levels.

“Being a socially responsible company is important these days, especially to younger employees and consumers,” says Barker.

Another example of a corporate partner she cites is the clothing and home furnishing retailer, DownEast, whose primary market is Millennials.

“In seven years, DownEast has contributed over $200,000 through employee gifts and corporate matching and the have sent their employees, including their founders, on four expeditions,” Barker says. “This year, the village DownEast adopted on their first trip has officially graduated from our program.”

What does Barker’s mother think of her daughter’s success?

“She is so proud,” says Barker, “because it’s all about giving back and passing on what I learned from her.”

Besides the importance of an education, what other lessons did Barker learn from her mom that she now passes along to young mothers?

“Be a good role model – your children are learning from you how to become adults.”

The Woman in the Market

The Woman in the Market

Published by The Writing Cooperative, March 25, 2017

“Who’s that woman over there? No. Over there. The platinum blonde selling the Provence linens, just past the spice vendor, opposite the flower stall.

“Who’s that woman over there? No. Over there. The platinum blonde selling the Provence linens, just past the spice vendor, opposite the flower stall.

The one whose legs are stuffed like sausages into those lace up, white vinyl, gladiator boots with heels. Doesn’t she know it is 95 degrees today? Those boys we passed along the way, the ones who were diving for coins in the river by the footbridge, they know how hot it is.”

“I bet she hawks linens by day and croons by night, a wannabe chanteuse in a second-class, smoke-filled bar, pining for when she was young and ran off to North Africa with the Algerian prince she met at the café where she worked as a waitress. Her father disowned her for that one!”

“No. She must be married to the butcher, that pig of a man selling sausages at the edge of the market. He probably told her to wear those ridiculous boots because it gave him a hard-on and he likes his women slightly stuffed.”

“She dumped him a long time ago for the salty haired antiques dealer with the deep set eyes who sells cleavers and other implements.”

“It’s probably just her cover and she’s really a spy. I mean, I didn’t see her last weekend and I made it almost all the way around the entire market. Those linens probably have codes written in invisible ink or computer chips or antique coins sewn into the hems. Coins. Maybe that’s what those boys were searching for in the river.”

“I bet those boys are her kids or maybe even her grandkids. She probably gave them a few coins to stop pestering her and sent them off to the boulangerie to buy bread for dinner. Of course they never made it to the baker and spent the money instead on ice cream...”

“...but not wanting to risk the hand of the butcher, their father, they decided to hunt for treasure among the river rocks so they wouldn’t have to fess up to their crime. But that’s another story.”

“No. I’m certain I saw her once in the pages of a magazine when she was a fashion model and those boots were still in style.”

© Sharon Spaulding. All Rights Reserved.

contact

contact linkedin

linkedin Instagram

Instagram

facebook

facebook